A thing I love as a device is the pre-existing trauma. Something foundational that renders a protagonist either unable to see the world as it is, or unable to see themselves as they are.

Trauma does this, it warps things. It warps perspective, it warps scale. Your entire metric of evaluating good/bad, normal/weird, definite/possible changes. Trauma makes you an unreliable witness, an unreliable narrator. An unreliable person. Spend a few years as a kid with your parents screaming that you’re a liar and you start to believe you are one. Or: you start lying. Because when it comes from the people who are supposed to love and care for you the most, it becomes true because those are the people who define what true is.

Gilly Macmillan is perfect at executing this.

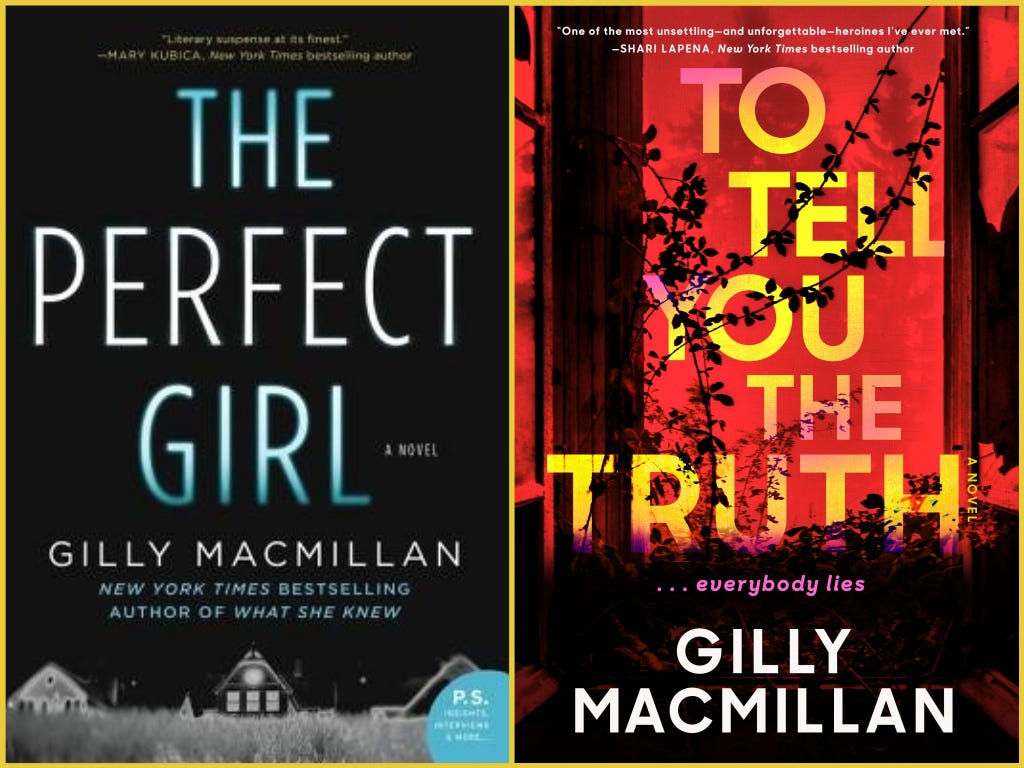

I found British writer and former Art Historian Gilly Macmillan in 2016, when I picked up her second novel, The Perfect Girl. (And sorry but the original title was Butterfly in the Dark which is way better and I just needed to get that out of my system.)

The Perfect Girl is about teen piano prodigy Zoe. Zoe drives away from a party not knowing that her coke had been spiked, and the ensuing accident kills the three teenage passengers in the car. Three years later, she is living with her mother and new stepfather, trying to get back to something like normal. On the night of her recital, her mother is dead, and Zoe’s past is revealed to everyone who didn’t know—including her stepfather.

Zoe is resilient (teens!) and you root for her, sure. But also her trauma keeps her from seeing what’s in front of her—she’s so fixated on what’s wrong with her that she misses what’s wrong with everything (and everyone) else.

It’s a brilliantly plotted book full of regular, deeply flawed people, told in short, sharp chapters. I loved it. And Macmillan’s new book is the first one to hook me as hard as The Perfect Girl.

To Tell You the Truth’s protagonist is a wildly successful mystery writer, but I promise that won’t be annoying for more than like four pages.

The fake writer’s name is Lucy Harper. Lucy’s trauma came in the form of her brother disappearing in the woods behind her house, when she’d snuck out with him to watch the solstice one summer night. He was never found, and Lucy, age nine at the time, was never not suspected in his disappearance.

To escape, she moved to the city, changed her name, married, put it behind her. Lucy writes a series of novels featuring a detective named Eliza, a character modeled after Lucy’s childhood friend. Problem is, Eliza is a little too real, a little too literal. She’s extremely real to Lucy: Lucy talks to Eliza when she’s alone, and sometimes, Eliza even speaks for her, a foreign voice coming out of Lucy’s own mouth in terrifying moments of conscious, waking paralysis.

But nobody knows this. Nobody really knows anything about her.

Except maybe Dan. Lucy’s husband Dan is the only person who knows about her missing brother. And he’s cool about it, until he starts acting weird. He buys them a new house without telling Lucy, and relocates them, uhhhh, really super close to where Lucy’s brother vanished. Dan seems to know some of the neighbors already, even as they’ve just moved in. He starts shit-talking her books, even though they paid for his precious new house in the suburbs and his fancy lifestyle.

Lucy notices all this, of course, but she doesn’t trust what she’s seeing. She isn’t sure it’s real. She isn’t sure if anything is real.

Just as Lucy starts to believe herself, to really process that Dan is being secretive and cruel, he simply vanishes. And then it all comes unglued: her secrets start leaking out, her career is at stake, she loses all of the control she once had over her immaculately controlled life. The shell-person she built around the trauma at her center is, in an instant, gone.

She has to navigate this new but suspiciously similar disappearance through the lens of the one that had already hobbled her mind and heart. She has to make her neighbors think she is grieving normally. She, in shock and increasingly unhinged, has to get in the woods she’s feared since her brother vanished and find the spot where she last saw him. She has to piece both mysteries together, because if she can’t, she’s on the hook for them both, and she knows it. She has to do it with paparazzi in her driveway.

She has to do all of this because telling the truth—the real truth about what happened with her brother, and perhaps using that to find her husband—is literally unthinkable.

What I love is how Macmillan’s characters cling so firmly to their interiority, and the notion that everything bad is always their fault forever. Zoe believes she is a monster for killing her friends, and so you believe it too, to the point of forgetting, almost, that she’s just a kid with adults who are failing her. Lucy believes that she must listen to Eliza, believes that Eliza knows things, and you believe it too. Because it’s really real to her. Installing that software kept her alive and she can’t uninstall it now.

This is what trauma is. It’s being afraid all the time, and being afraid to tell people you’re afraid because they might try to convince you not to be. It’s constructing a reality where nobody can ever get between you and your fears, even if it means never fully letting anyone in. It’s a nightmare of clinging to the edge for dear life even though anyone looking at you sees two feet planted firmly on the ground.

Throw a new tragedy at this type of unreliable narrator, force them to navigate it through their warped lens, take away their coping mechanisms, set it in the woods amid creepy old underground bunkers, and you’ve got To Tell You The Truth—deeply atmospheric, intense, dark, haunted, Gilly Macmillan at her best.

To Tell You the Truth is out on September 22nd. Buy it here, along with the rest of Gilly Macmillan’s books (they are all good).

Recently read: The Enduring, Pernicious Whiteness of True Crime / Elon Green

Recently heard: Attack of Panic / Aly & AJ

Recently cooked: Peaches and Cream Pie

Recently recorded: Sister Golden Hair Surprise